Thy flesh consumed

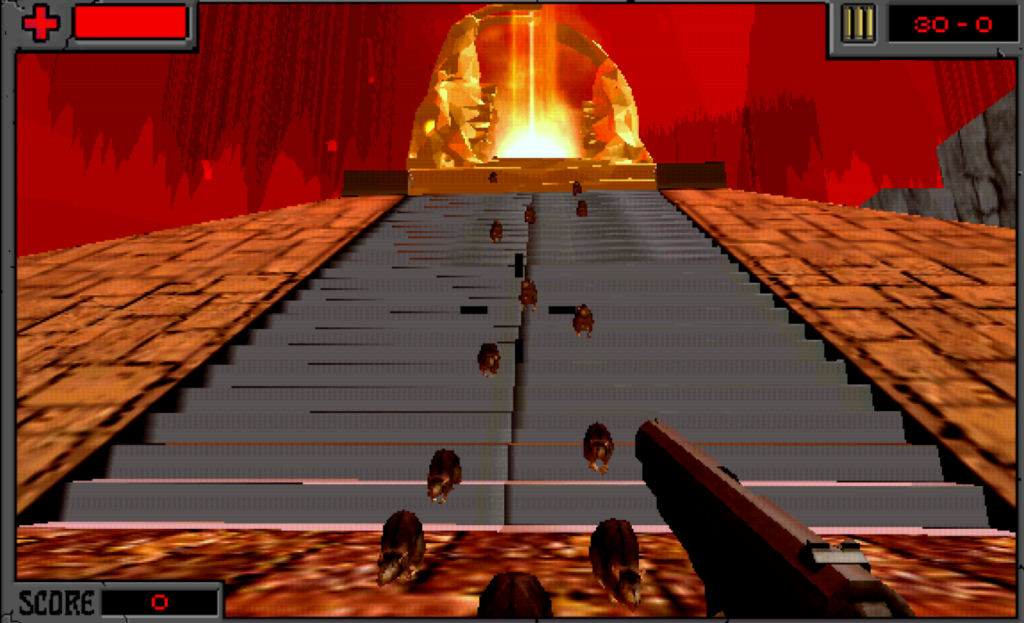

A simple browser game, styled after DOOM clone shooters of the early 90’s, MARS FOR THE RICH is promotional material for the song of the same name. Leaving an antechamber filled with nondescript wooden crates, the player – armed with a handgun – enters a sunken arena of floating stone and blood red sky. At its center, a pyramid and a golden statue.

Scaling the pyramid steps, empty gun in hand, the player finds the statue composed of two golden skulls flanking a floating bullet with a gold casing.

Interacting with the bullet pushes you back down the temple, and returning to the top to try again triggers the action of the game, loading you with 30 bullets and releasing an enormous swarm of rats from the pyramid.

“Mars for the Rich” begins playing, and you navigate the area, kiting the swarm as you fire hundreds of bullets into the mass of rodents. Consuming glowing fruits and ammo pickups enable you to continue fighting after taking and dealing damage. The game becomes increasingly hectic as the swarm steadily grows, until large three-headed flying rats rain fireballs down on the player.

5000 points in, multiple three headed giant flying rats down, and two turns of the song later, there’s no victory screen in sight. By now the point is clear: you won’t outrun the horde, and they won’t stop coming.

The song itself, off the fifteenth album from rock band King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard, is sung from the perspective of a “poor boy” on a “deformed” Earth. The narrator contrasts their life laboring in fields with “blistered fingers” to wealthy Tsars on TV who live happy, luxurious lives on the terraformed red planet.

The metaphor is clear, and apt; the player takes on the role of the elite on mars, the horde of rats becomes the poor and unwashed Earthlings, invading the sanctity of Mars to consume their oppressors. Individual rats die, but no matter how many clips the player unloads into the crowd, the many eventually overpower the few.

Infest the Rats Nest follows the promotional game soundly, with A-side tracks like “Superbug” in reference to the rise of drug resistance in response to human use of antimicrobials and “Planet B” in obvious reference to the drive for space colonization in response to climate crisis. The album has a clear thesis: while they’ve let Earth become unlivable, the Earth’s capitalist class have turned their attention to the stars, in hopes of escaping the consequences of their (in)action. For millennia, all of humanity has stared up at the night sky in wonder and adulation; since when did the heavens become the playground for the few, and not the many?

Two visions of the future

Gabrielle Cornish writes, “How Imperialism shaped the race to the moon” (for the now billionaire owned Washington Post) detailing how from humble beginnings in 19th century Russia through the tumultuous revolutionary period and onto the established Soviet Union, narratives of space exploration in a revolutionary and socialist context differed drastically from American-Imperial narratives. The Soviets scoreboard boasts the first space probe, the first person in space, first woman in space, the first black person in space, and more. All this while, the soviets were producing propaganda which emphasized space exploration as the culmination of humanity’s collective labor.

Losing the space race by most metrics, American artists, authors, and propagandists were pressed to win the cultural battle surrounding the space race. We planted a flag on the moon, and went about convincing ourselves we had won by producing our own alternative utopian visions of outer space.

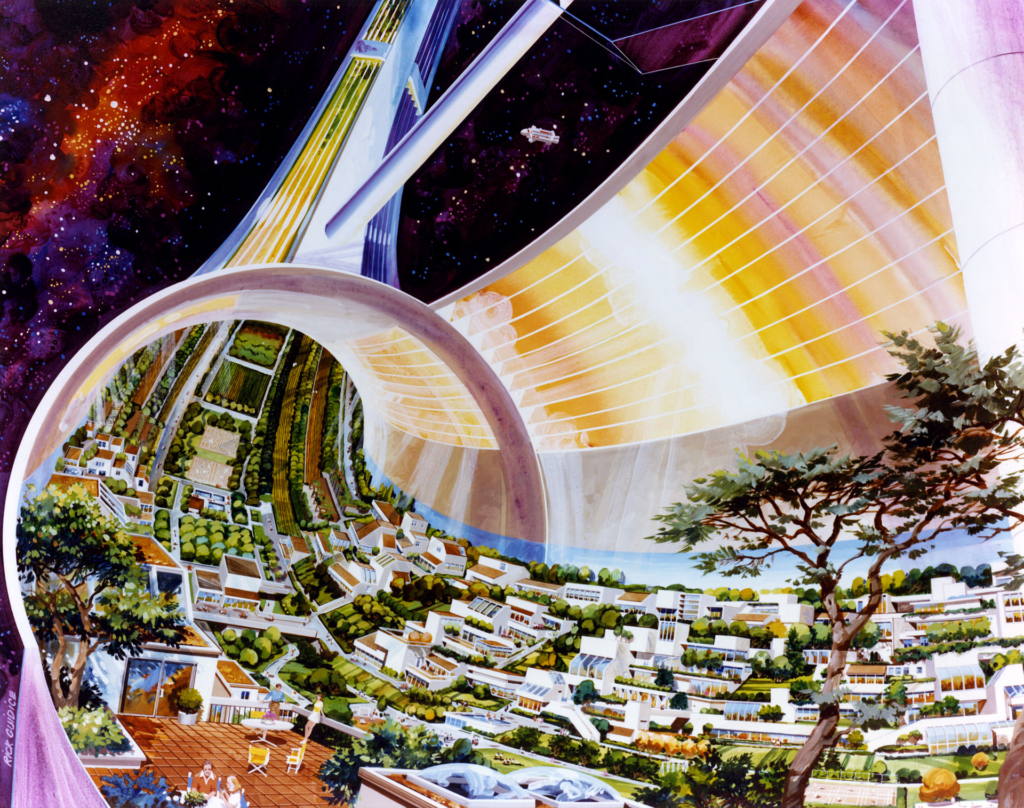

One immediately calls to mind the Stanford Torus, a NASA concept design for a space colony that generates artificial gravity for its residents using centrifugal force. Artists depictions of the design, particularly the residential cutaways, have become synonymous with a retro-futuristic pining for luxury space travel in the 21st century, showing vast sloping stretches of verdant urban sprawl enjoying the bright, almost Californian, simulated-Sunlight, millions of miles from terra firma.

The Jetsons – like their real world contemporaries, middle-class white Americans, living sweet off of a postwar boom – model the future after the individualistic, consumerist, capitalist present. The only difference, is that there aren’t any poor people on the Jetsons. One might morbidly wonder where they went.

These overlapping, reinforcing cultural narratives of a sterile, utopian Outer Space paved the conceptual path for private interests like SpaceX, BlueOrigin, and VirginGalactic to propose their own brands of elite, comfortable, and exclusive space tourism.

Militarization & Privatization

“I would annex the planets if I could”

Cecil Rhodes

In today’s age, science enthusiasts are bombarded with articles from science websites and major publications with titles like “Elon Musk Beats Jeff Bezos To U.S. Air Force Contract As Billionaire Space Race Blasts Off”, or “Blue Origin Launches Its First Space Tourism Rocket In Seven Months – And Hopes To Take Humans To Space In 2020”, and “SpaceX’s Mars Colony Plan: How Elon Musk Plans to Build a Million-Person Martian City”.

The space race rallying cries for this century frequent the science fiction of the past for inspiration, where capitalist realist visions of endless resource extraction, military domination, and human/American exceptionalism find a broad audience. Terra-forming, mining, and the frequent destruction of celestial objects feature heavily; the irreparable destruction that is depicted in science fiction mimics our own Holocene extinction event with vanishing self-awareness. Heinlein’s fascist, 1959 military science fiction classic Starship Troopers does the conceptual legwork for a militarized cosmic frontier. Thankfully for the troops, only 40 years later the wit of Paul Verhoeven would thoroughly dismember Heinlein’s heroic vision on the silverscreen.

In the sixth chapter, “Prospecting the Final Frontier,” from her book The Global Interior: Mineral Frontiers and American Power, author Megan Black explains how the department of the Interior, born of the need to direct and control corporate led settler-colonial expansion in the 19th century, collaborates with NASA not only to prospect Earth from the heavens, but to prospect the heavens themselves. Black writes,

“…the Johnson administration and the space bureaucracy began touting extra-terrestrial minerals—seemingly boundless and, equally helpful, inoffensive. Celestial bodies were not populated, after all. In April 1964, a deputy administrator of NASA, Hugh Dryden, told the readership of the New York Times, ‘Geologically, we have no reason to doubt that the moon and the nearby planets, being solid bodies, may be rich in rare mineral resources, possibly offering economic returns far outweighing the costs of exploration’” (page 188).

Private spaceflight companies, like SpaceX, deal primarily in military contracts and public subsidies, which allow them capital to afford their forays into private, luxury spaceflight projects to soothe the nerves of their anxious shareholders and executives. Trump administration’s Vice President Mike Pence, writing in the Wall Street Journal, said, “In the years to come, American industry must be the first to maintain a constant commercial human presence in low-Earth orbit, to expand the sphere of the economy beyond this blue marble.”

A colony by any other name would be just as sweet

Make no mistake, the rhetoric of colonization applied to space exploration is no lapse in judgement. While many writers (like those mentioned below) have written well on this topic, their analysis focuses heavily on the rhetoric of Musk, Bezos, and space colonization. They are predominately concerned with problematizing the cultural narrative, and not the foundations of that narrative, namely existing colonialism and imperialism, looking to release the pressure they’ve generated on the Earth with their greed out, into the vacuum of space.

Writing for her series “The Urban Scientist” in Scientific American, Dr. D.N. Lee says “When discussing Humanity’s next move to space, the language we use matters.” Here she details,

“Elon Musk’s vision for the humanity and colonizing Mars makes me incredibly uneasy. It’s not that Elon Musk has said very many inappropriate things, it’s that so much of the dialogue about colonizing Mars – inspired, initiated and often influenced by Musk – uses language and frameworks that are a little problematic.”

Lee’s article provides important pushback against Musk’s dominant media narrative, and uses this issue as a wedge to discuss important matters of diversity in STEM. Still, I can’t help disagree in one key aspect; Musk’s language and framework is harmful precisely because he says and does inappropriate things. Notable for suppressing unionization at his Tesla factories, Musk’s fortune is the byproduct of a Zambian emerald mine his father owns, and he grew up privileged in apartheid South Africa. Its precisely his position of power, a billionaire who predicates his wealth on the expropriation of the labor of his workers, which informs his rhetoric. He says the things he says, because his words protect his own interests. Musk is at best a useful idiot for multinational capital, drawing public attention away from the horrors of late-capitalism by smoking weed on Joe Rogan or fighting with his wife on twitter. At worst, he’s a ruthless exploiter who sees the expanse of the Solar System as his corporation’s birthright.

Missing the point, Keith A. Spencer, writes in Jacobin, “Sure, let’s colonize Mars — but without Elon Musk’s help.” Spencer, who covers the topic of privatization of spaceflight across many publications, correctly recognizes the failures of previous colonial ventures, saying “Indeed, when it comes to colonization, we should hope humanity has learned from its past mistakes and is ready to set upon a more democratic process. Perhaps Earth can agree to hold a public discussion before we set about strip-mining Mars’s glorious dunes, vistas, and mountains, lest the tallest mountain in the solar system become a trash heap like Everest.”

Yet, Spencer’s advocacy trades privatization for government agencies. Instead of private companies, Spencer tees up NASA to lead ventures to “colonize Mars.” We shouldn’t let Phelps Dodge colonize the West, we should let the Department of the Interior manage it!

Falling short as well is Caroline Haskins’ article in the Outline, “The Racist Language of Space Exploration.” Haskins’ article, like Lee’s, is thorough and convincing, but it falls short by historicizing colonialism. The thing to understand is that colonialism is still being actively resisted all across the world because it is still ongoing. In this way space exploration/colonization from any colonial power is therefore a perpetuation of ongoing colonialism.

The above authors accurately capture the uncomfortable truth: american dreams of colonizing the Solar System on the back of SpaceX rockets resemble those of the 19th and 20th century western expansion, and carry all that baggage. Recognizing the material reality, however, is perhaps more immediate to our ongoing struggles with climate change and inequality. While the rest of the solar system may not be populated like the Earth is, colonists invading ecosystems and claiming terrain they have no practical understanding of has historically gone poorly. As I write today, wildfires which were once regulated by indigenous practices consume the western states, blanketing my hometown of Portland, OR in heavy, reddening smoke. The same extractive and destructive process, even in the absence of ecologys as we understand them on the Earth, would spell disaster for microbial life that might exist in the solar system, not to mention the destruction of landscapes that have persisted for millions of years. And, as Mars of the Rich reminds us, even if luxury spaceflight is made reality, luxury requires labor, and labor as we understand it today requires exploitation. Woe to those workers forced to porter today’s ruling class across the heavens.

Science enthusiasts, astronomers, and conscious consumers of media must be able to recognize when a problematic rhetoric points to a deeper injustice. We can’t allow the colonization of the solar system in any way, by corporation or capitalist government, just as we can’t allow the colonization that is ongoing on Earth. The Mars for the Rich mentality now sold to us by wealthy white billionaires isn’t the product of a few evil men using bad language, it’s the logical conclusion of an imperialist state, forced always to find some new frontier, less it be consumed by the rot at its core. Remember: We’re the rats. Its time to feast – maybe before they board the rockets.

Update: 9/14/2020 – A good friend of mine, Frank Tavares, whose game when you arrive remains one of my favorite pieces of electronic literature of all time, published a similarly fantastic white paper titled “Ethical Exploration and the Role of Planetary Protection in Disrupting Colonial Practices” which makes a case effectively for considerations pertaining to much of what I discussed in this article. I’ve linked the draft here, and if you’re looking for some material closer to the heart of the astronomy community (not that my blog isn’t an important pillar of the scientific community) I’d give it a read.

Update: 10/12/2020 – was pointed to this great comic/article in the nib that was posted last year. check it out!

Update: 12/19/2022 – I made some edits throughout to improve readability, and slightly tweaked the title.

Leave a Reply